Chapter 0: Directed Graphs#

Note

This book is a work-in-progress! We’d love to learn how we can make it better, especially regarding fixing typos or sentences that are unclear to you. Please consider leaving any feedback, comments, or observations about typos in this google doc.

0.1 What is a directed graph?#

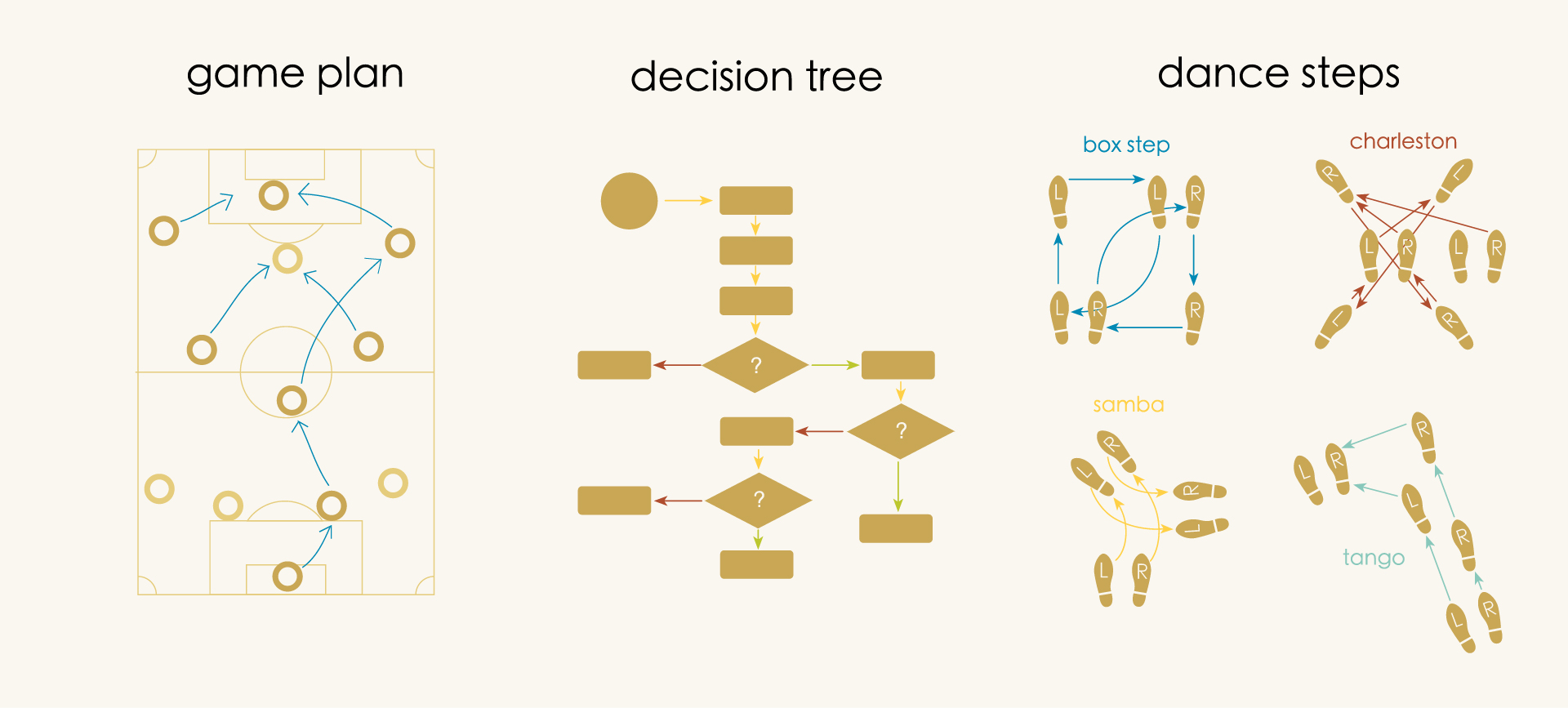

What do these diagrams all have in common? First, they all have arrows. Second, they all have some “points” (players, footprints, questions, etc.), and every arrow connects one point to some other point. This is our starting point into relational thinking and AlgebraicJulia, a simple modeling system called a directed graph.

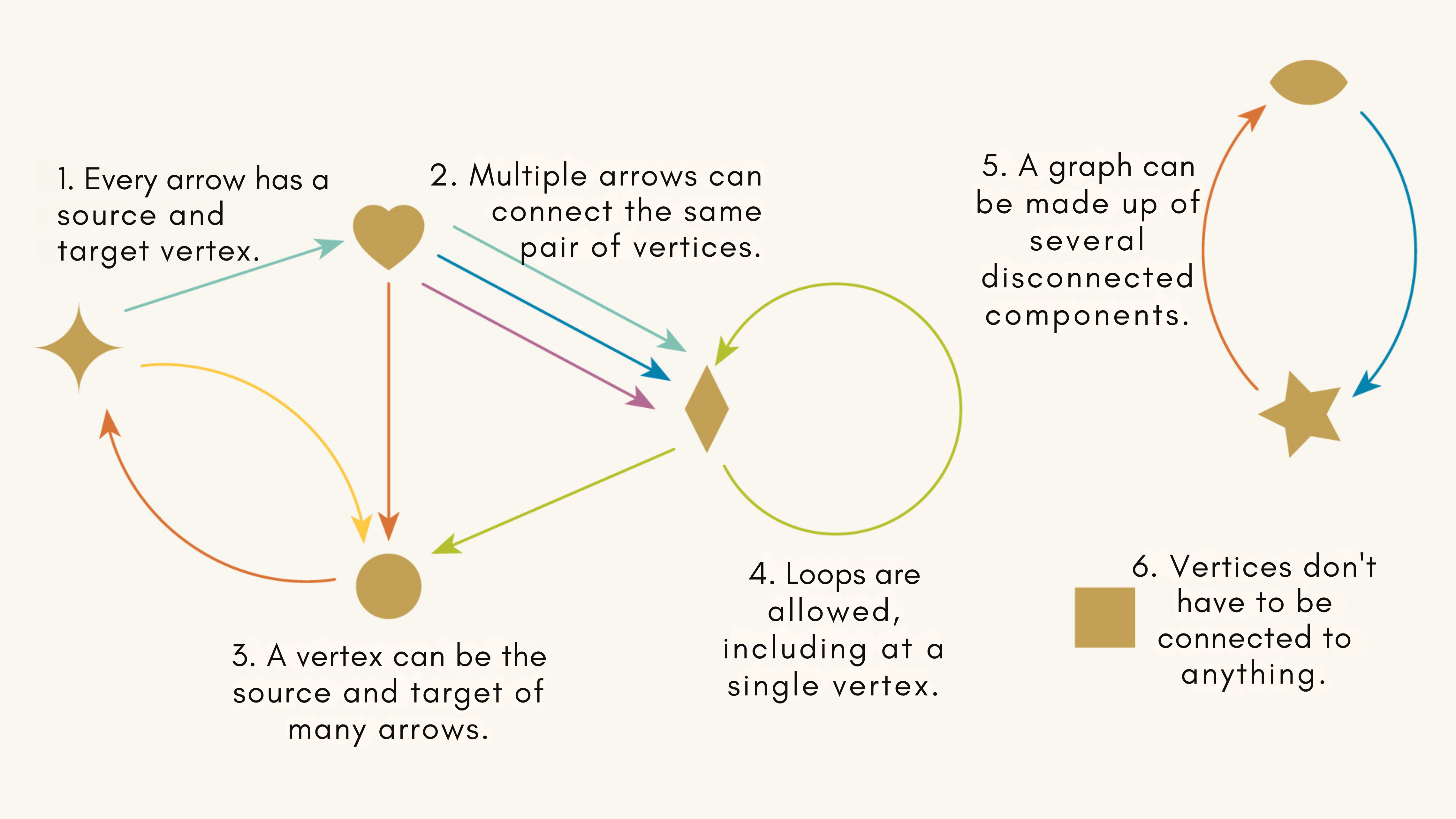

In the language of directed graphs, the points are commonly known as “vertices” (”vertex” when singular). What makes up directed graphs are collection of vertices and arrows, a few simple rules that they follow:

It’s a simple setup but many situations in life - many systems - are well-captured by this kind of diagram.

Consider how we can use directed graphs to represent the following three situations:

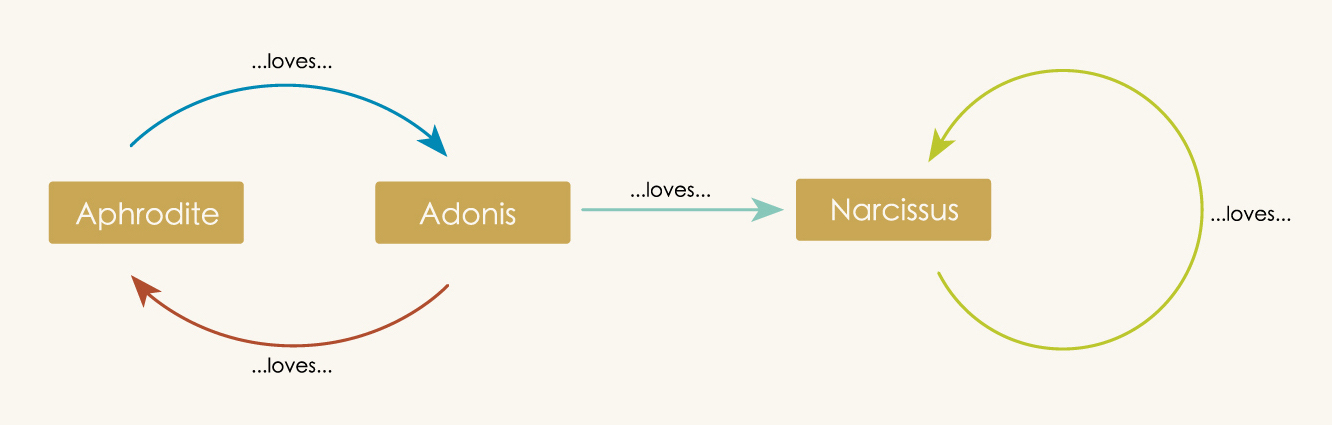

Mythological Romance

Aphrodite loves Adonis and Adonis loves Aphrodite. But Adonis is polyamorous and is also in love with Narcissus. And Narcissus, of course, loves only himself.

We can make a directed graph of these relationships in which the vertices are characters and an arrow indicates that the person at the source loves the person at the target.

Ski Trip Brochure:

From our ski lodge, you can take the lift to the top of the mountain. Skiing down the slope will take you to an isolated Alpine village in a valley where you can cross-country ski around the surrounding landscape. Of course, some people don’t know how to ski. If that sounds like you, don’t worry! You can still visit the mountain top to see the beautiful view and then just jump back on the lift and return to the lodge.

In this directed graph, the vertices are locations and the arrows are “modes of transport” from one location to another.

If you squint, you can look at this like a simplified map. We’ve left out the trees and the geography and the distances from one place to another. We’ve distilled our way-finding to only the most essential details needed for getting around.

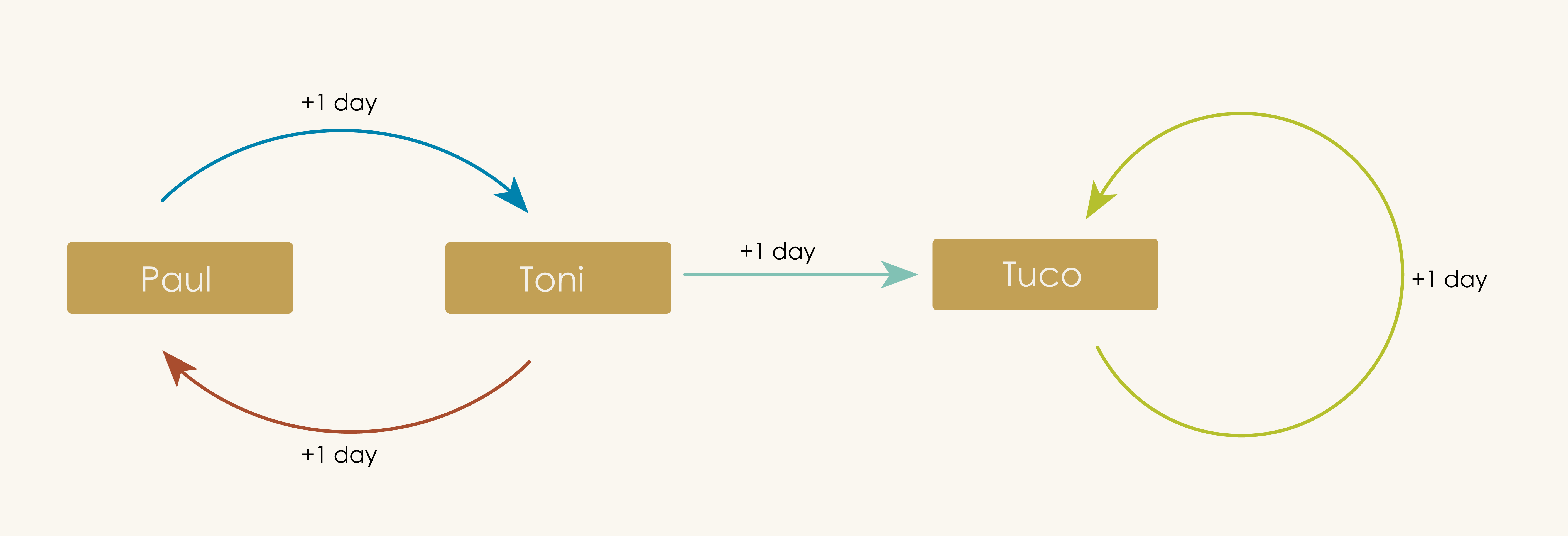

Whose Turn Is It To Do the Dishes?

Paul and his wife Toni used to trade off doing the dishes each day. Then their friend Tuco moved in who loves doing dishes and he has done them ever since. Toni was the last one to do the dishes before Tuco took over.

In this directed graph, the vertices are once again people and each arrow connects two people who may do dishes on consecutive days.

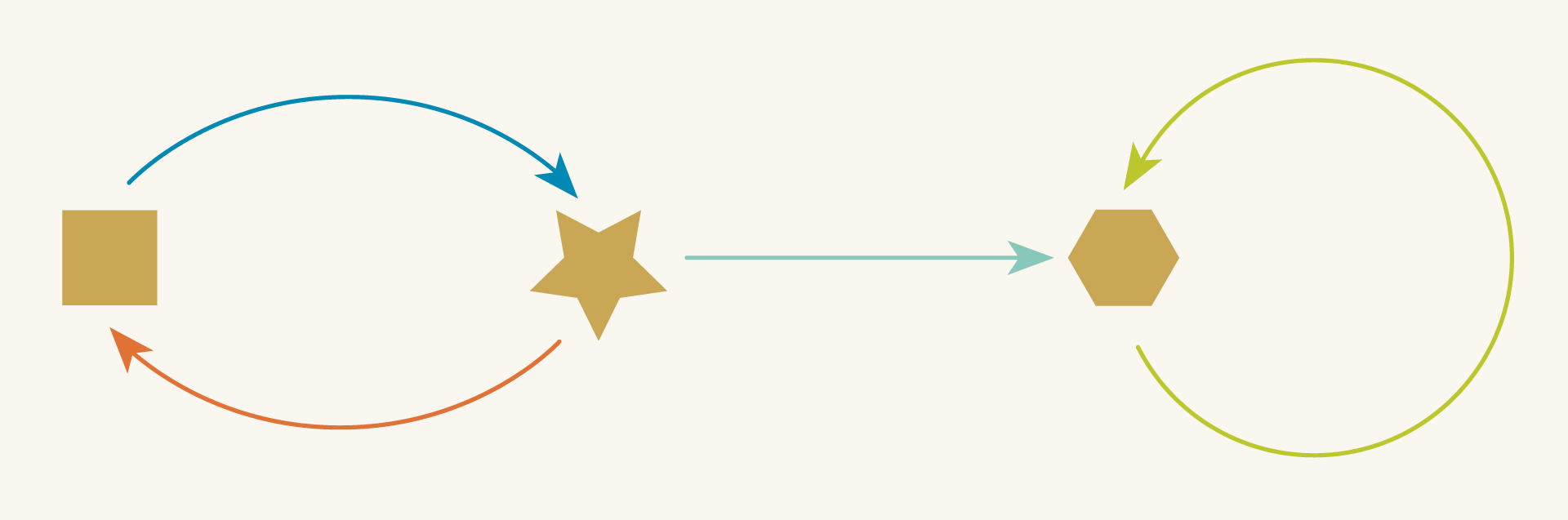

Looked at individually, each of the above situations seem quite different. But their directed graphs make it clear that they all share the same essential structure. Abstractly, they are all the same graph, which we can represent in unlabeled form:

When used casually like this, directed graphs are little more than convenient pictures. They are visual heuristics that make it easier to think about the underlying situations. Over the course of this book we will transition to a more formal point of view, unpacking the capabilities of AlgebraicJulia through an extended look at directed graphs and related ideas.

0.2 Why directed graphs?#

Why are we choosing to focus on directed graphs?

In one sense, directed graphs give us a nice combination of simplicity and versatility. They are easy to understand and rich in terms of applications. They are conveniently pictographic, allowing us to make pretty illustrations, but are also a powerful formal tool, something that can be communicated to a computer in order to model complex systems. As we try to get a sense of what AlgebraicJulia is all about, it is helpful to be working with something that is both accessible and deep.

But the real reason we want to look at directed graphs because they are fragile.

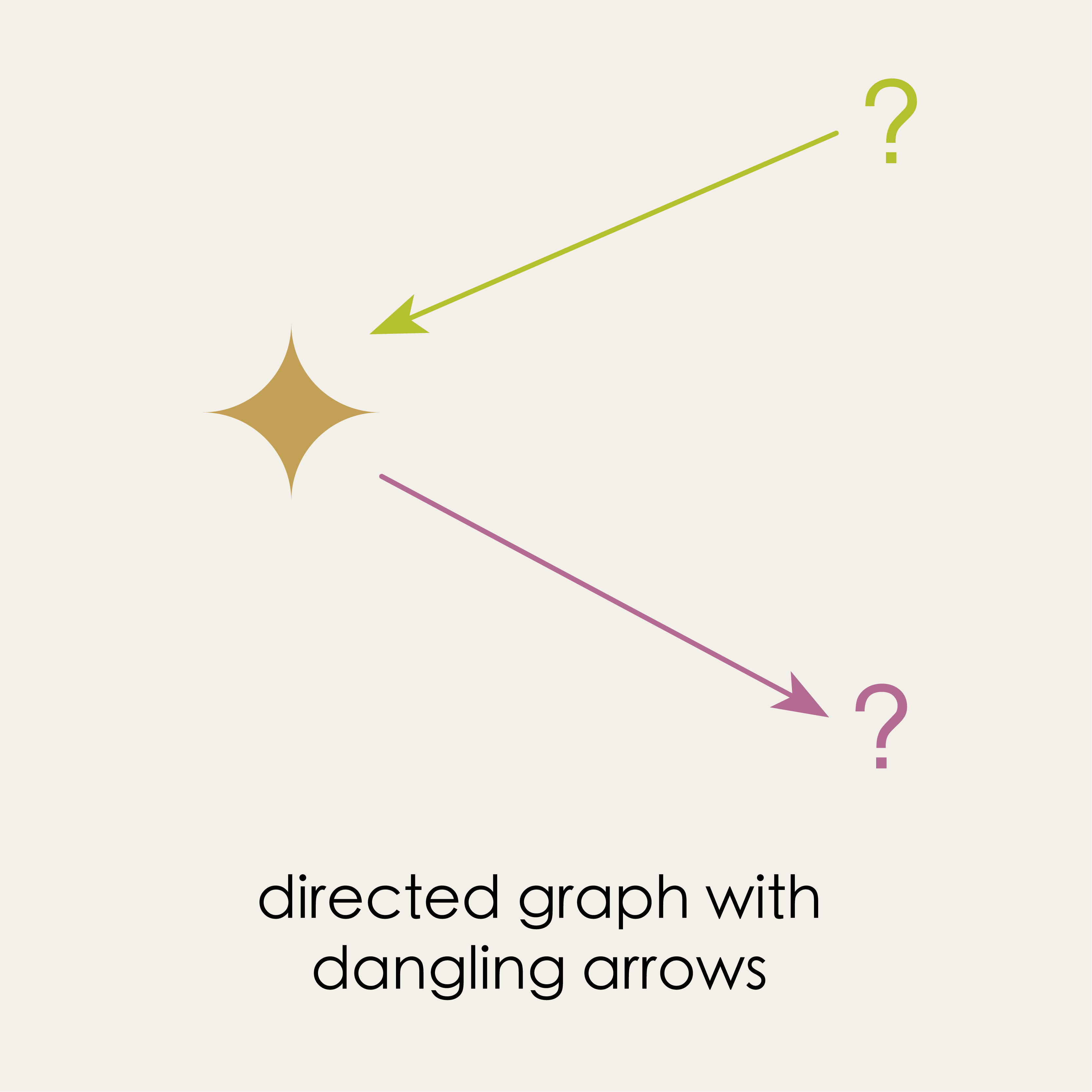

Suppose we’ve modeled some situation in a computer using a directed graph. If our understanding of that situation changes then we’re going to want to update the details of our graph to reflect this new understanding. Specifically, we’ll need the ability to add or delete arrows and vertices as necessary. Now, modifying a graph is a non-trivial problem. If we follow a procedure that allows to freely add and delete graph components, we may end up with broken graphs – graphs with arrows no source and/or target!

By definition, the arrows in a directed graph must point from one vertex to another. But if we’re not careful we may update our graph in a way that leaves arrows “dangling.” When we’re trying to model the world with a directed graph, a broken graph like this is a big problem because it invalidates the underlying model. It’s not that the model becomes incorrect. It becomes meaningless. To say, “Aphrodite loves …” is not right or wrong, it’s just ungrammatical!

And an unfortunate fact of life is that directed graphs in a computer are prone to getting broken in this way. We can try to exercise care when performing simple updates, but more sophisticated computational manipulations–merging graphs, separating subgraphs, performing replacement on sections of graphs–all of these introduce complicated edge cases in which arrows and vertices may end up becoming detached.

We will call this our DANGLING EDGE CONDITION.

This is a book about a powerful and elegant solution to this problem which exercises relational thinking. In our final chapters we will arrive at the concept of a double-pushout rewrite rule, a category theoretic design pattern that will allow us to perform intricate replacement of sections of graphs without having to give a second thought to the problem of dangling edges. Unfortunately, this tool exists at a level of abstraction that most people are simply not accustomed to thinking about. We will have to move through certain layers of abstraction to get where we’re going, developing new ways of thinking with help from AlgebraicJulia along the way.

AlgebraicJulia is being developed as an ecosystem for serious scientific modeling. But in order to use AlgebraicJulia effectively you need to have some sense of how to organize your thoughts while writing programs with it. We wrote this book to show how a simple and chronic practical problem - the DANGLING EDGE CONDITION - can be handled elegantly from a relational viewpoint using AlgebraicJulia. We hope this simple example gives you a taste of how categorical computation works and an appetite to find out more.